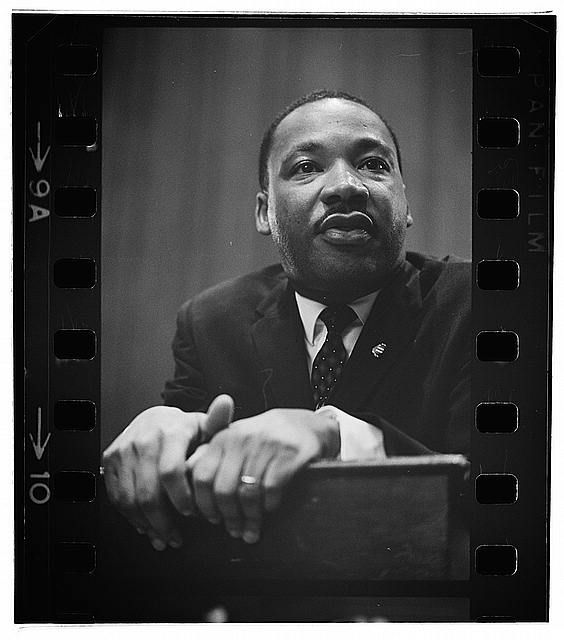

Len Chandler was a protest singer, movement worker and unsung hero from the Civil Rights Era, a frontline campaigner in the fight for voting rights, racial and economic justice and against wars of aggression. He performed with Bob Dylan and Joan Baez at the March on Washington For Jobs and Freedom in 1963 where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his historic “I Have A Dream” speech. In 2021, I was commissioned to write a piece on Chandler and his relationship to Bob Dylan in front of the opening of the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, OK. The essay is emerging here for the first time before its publication as a commemorative limited edition booklet on the life of Chandler (with illustrations and expanded content). A portion of the book’s earnings will be contributed to voting rights organizations, but for a limited time, we’re offering an early read of the book here, in memory of Dr. King and Mr. Chandler.

“You have to take the lead from somewhere and there were only a few performers around who wrote songs, and of them, my favorite was Len Chandler,” wrote Bob Dylan in his book, Chronicles.

Among the singing foot soldiers in the civil rights movement, the students and teachers from coast to coast who sat in, stood up and rode on freedom’s highway, and of all the folksinging pamphleteers and poets who swarmed Greenwich Village in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, only Len Chandler emerged from that fabled period an under-looked groundbreaker and a foundational freedom singer, a kind of cosmic twin to Bob Dylan.

“We talked all the time,” said Chandler. “I can’t remember what we talked about but half the time, it would be philosophical, our different approaches to things. We could talk for two days on whether it’s a straight line or circle,” he said, recalling that vortex, that wrinkle in time in Greenwich Village where the cultural happenings of the ‘60s were beginning to reveal themselves. “I’d argue today that it’s a circle. The circle is built into everything. It’s built into our DNA, it’s built into the way the cosmos is formed. Everything is circular.”

The Village swirled with poets, playwrights, and artists of all stripes, mixed with locals and others from afar, far-out people who sought a fluid place to become who they thought they were meant to be – the kind of place and kind of time where young Len Chandler (from Ohio) and young Bob Dylan (from Minnesota) could meet, become friends and learn how to frame, shape and deliver a song.

“He sang quasi-folk stuff with a commercial bent and was energetic, had that thing that people call charisma,” Dylan wrote. “Len performed like he was mowing down things. His personality overrode his repertoire. Len also wrote topical songs, front-page things.”

___

“I first saw Dylan at the Cafe Wha, playing harmonica with Fred Neil and he would occasionally play a Guthrie song by himself. We’d sit in bars and I’d be reading the paper and underlining stuff,” said Chandler, a classically trained musician who developed a new skill in the Village and beyond it. In Greenwich Village he spun stories out of headlines and, ultimately, his lived experience as a Black man in America.

Raised to fight for racial justice in his hometown of Akron, Chandler would find his voice as a topical songwriter in Greenwich Village, and then make his way to the frontlines of the historic Southern voter registration drives in Georgia, Mississippi and Alabama. There he discovered that his voice could move a crowd of thousands. Despite no training as a community organizer, nor any background in old time religious singing styles, after his performances down South, Chandler was pulled into the fight for civil rights on the strength of his ability to deliver a song. From thereon, he became a lifelong movement worker.

“I considered myself a bourgeois Negro from the north,” he said, “Writing allegories and abstractions.” Fearing his “esoteric metaphors” wouldn’t fly at mass gatherings, his songs nevertheless proved useful. They are also timeless, alive and immediate in a never-ending struggle and commitment to seeking justice. In originals like “Keep on Keeping On,” with its spirit of melancholy fused to resilience and adaptations, and in his righteous rewrite of the sacred “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize,” Chandler’s voice rung out strong, speaking to the marchers and leaders of their time.

Read it in the paper the other day

Things are swingin’ in the USA

Keep your eyes on the prize, hold on

Chandler’s performance at the March on Washington, with Dylan and Joan Baez is a piece of that history, as are his solo albums To Be A Man and The Loving People, both released in 1966 on Columbia Records.

But while Dylan and Baez moved deeper toward their destinies, to be feted and appreciated, all over this land, Chandler lived a life largely masked and anonymous, his work as musician and activist remaining unsung, though he was no less committed to serving as a liberatory voice for the people.

“Len was brilliant and full of goodwill,” wrote Dylan. “One of those guys who believed that all of society could be affected by one solitary life.”

There are things to be done there are things to be said

Some may live a long time but we’re all long time dead

I think of the things that I’ve thought done and said

And I think of the time I’ve been wasting *

___

“There was a time we saw each other every day,” remembered Chandler, whose own arrival in the Village in 1958 was more an accident than Dylan’s intentional embarkation in 1961. Through a series of uncharted events Chandler stayed, fell into the crowd and became a folksinger, one of the few on what was at the time largely a poetry scene.

“Len was educated and serious about life,” Dylan remembered. “Was even working downtown with his wife to start a school for underprivileged children.”

“I knew the possibility of being able to sustain myself as a player was slim,” said Chandler. “There was only one black player in a major symphony orchestra at the time. Even if you’re white, it’s difficult to get the oboe chair. You have to apprentice with the major player and be the understudy until he retires or dies.” He set his sights on teaching.

Born in 1935 to parents he describes as laborers, “My dad got home at six in the morning, had another job from seven to three, would take a nap, then play saxophone from eight to two. He had played in the Tuskegee Band. My mother was a beautician and then got a job at Goodyear.”

As an Underground Railroad stop for slaves in flight to Canada, Ohio has ties to abolitionists John Brown and Sojourner Truth. In the 20th Century, Marcus Garvey found a base of support there for his United Negro Improvement Association. But Chandler did not receive a particularly Black-centered education; rather, his Akron was rich with cultural offerings more European in origin: classical music, theater and opera. It was by chance, while working as a page at the public library, that he discovered the poetry of the Harlem Renaissance and Langston Hughes as a teenager.

“I learned piano when I was nine and started taking regular classical lessons, ‘Clair de Lune,’ all that,” he said. “I got a job ushering the Tuesday Music Club, where they brought in the orchestras, Vladimir Horowitz.”

The Chandlers spent summers in Idlewild, the historically Black resort in upstate Michigan. “Everything else was closed to Black folks,” he said of a time when beaches and pools were segregated. “While other kids were in summer band, I’d be away. By the time I got back to school for an instrument, they were all gone and a guy said, ‘here’s this,’ an oboe with a Pan-American fingering chart.”

As a senior in high school, Chandler was playing with the University of Akron orchestra; he had also participated in civil disobedience for the first time. And while the case against Summit Beach Park was won, the action was the last time Black and white kids swam together. “The pool was filled with cement,” he said.

At college he was a player with the Akron Symphony, but the one thing Chandler was not playing, and was not interested in was folk music (though he’d played a folksinger, a one-man Greek chorus, in a college production of The Rainmaker, the story of a con man claiming he could bring rain to a drought-stricken town).

“We got this great write up and then this guy came up to me and said ‘How’s your mama?’ What?! He said, ‘Look I heard the music you wrote for The Rainmaker, but I’ve got some stuff you need to hear,” explained Chandler. “This guy was a professor from the university who was doing a doctoral dissertation on The Dozens. ‘You help me collect these dirty dozens, and I’ll make my record collection available to you.’”

The record collection of blues, folk, and specifically country blues included Big Bill Broonzy, Sonny Terry, Mississippi John Hurt, Lead Belly and Son House. At the time, “That music hadn’t crossed my radar at all,” said Chandler.

In 1952, the Anthology of American Folk Music was issued. The highly influential collection compiled by Harry Smith and released by Folkways Records would contribute to an ascendance of roots music and the resuscitation of the careers of some of its living blues and mountain music players. At the dawn of his folk process, Chandler could not possibly know then that in just a few years time he would be sharing stages with some of these musicians and participate in the handing down of songs from one generation to the next. Further fueling its intrigue, Smith’s liner notes were crafted like headlines, screaming in all caps the details of the song’s stories. So “Engine One-Forty-Three” by the Carter Family, was distilled into the sensational, GEORGIE RUNS INTO ROCK AFTER MOTHER’S WARNING, DIES WITH THE ENGINE HE LOVES.

“I went to some bougie black church in Akron where the minister only wanted us to sing Bach, anthems…it was their vision of upwardly mobile, going to college, striving to be middle class.”

The dilemma of Black folks seeking to fit into a prescribed set of so called societal norms was a result of a deleterious “double consciousness,” the term used by Black scholar W.E.B. Du Bois to describe seeing one’s self through the eyes of the oppressor. Chandler described his experience of double consciousness in musical terms.

“You don’t recognize it till later, but people put you into the hands that are going to shape you artistically. They sent me to voice school…Enrico Caruso, George London…telling you how to make tones, where to put your tongue and mouth and how to position your head and make notes ring in your head,” he said. “You have to unlearn and imitate other stuff and then who am I being?”

The process of his unlearning was about to begin.

The university of Ohio professor who befriended Chandler had some upcoming business in New York and offered him a deal. “The guy said, if you’ll help me with the driving, I’ll pay for everything,” said Chandler. “He took me to New York and I got a job at Columbia University as an elevator operator for the summer. He took me to Greenwich Village, to Izzy Young’s bookstore on MacDougal Street. This guy with his hair all hanging in his face was playing the guitar. It was Dave Van Ronk.”

“I’d do my elevator operator job, get about four hours sleep and run back,” said Chandler. “After the summer, I got another job as a counselor for boys, the St. Barnabas House at Bleeker and MacDougal,” a home for women and children in need. “I would take care of the kids, bathe them, do homework, and walk them to school.” Between graduate studies at Columbia, “These eight- to eleven-year-olds were under my care every day and I took them to Washington Square Park to roller skate. And when they were skating, I started playing and singing on the square and people would come by and listen.”

Among the passerby was the “psychedelic clown” who’d come to be known as Wavy Gravy.

“Hugh Romney said look, we’re going to Hartford with poets and we want you to come. But you gotta dress down, dress hip,” said Chandler. “I picked up some black slacks and a red shirt, like Harry Belafonte,” his idea of a folksinger. “Hugh said, no man, that ain’t it.”

Romney pointed him to Orchard Street where he could find black jeans, chambray work shirts, black boots and a bandana for the neck.

“That became my folk costume,” said Chandler. “After that he asked me to play between the poets at the Gaslight. It was a whole poet’s scene late ’58-’59, not singers then,” explained Chandler, who performed with Romney and humorist John Brent. “Cafe Wha? was always a poet’s scene.”

He met Bob Kaufman, who would become a noted Beat poet.

“’Green Green Rocky Road,’ I wrote with Bob Kaufman.” The pair rooted their song in a children’s melody from the Georgia Sea Island/Gullah tradition and turned it into a contemporary folk standard, popularized by Van Ronk.

Van Ronk would later recall Chandler as one of the few Black folksingers on the mostly white scene. One night after a gig at the Gaslight he was jumped, though he survived the attack, owing to his experience with the “lateral drop,” a wrestling move he learned as a youth. On another occasion, he wasn’t so lucky.

“When I got beat up, my head cracked,” he said. “Dylan and Jack Elliott both came to see me at the hospital.”

To strangle in minutes and hours to drown

In years and in months for the last time go down

out of touch out of taste out of sound

with no echo and casting no shadow *

While folksingers of the time often traded in traditional songs, Chandler had started developing another survival skill: Turning his experience into verses of song.

“A guy came into the Gaslight and started heckling the poets. So when I got up, he started on me. I would take everything he said and tie it up in a blues verse just to cut him down.”

After some revelations and negotiations, the guy turned out to be a talent scout. Chandler was offered and accepted 13-weeks on Detroit late night TV-WXYZ.

Chandler set out for Detroit with a limited repertoire he was just staring to learn.

“In Detroit, I’d go to the library every day, listen to Folkways records by Cisco Houston, Woody Guthrie and fell in love with Gary Davis,” he said. “I’d learn a new song every day and sing it on the TV that night.”

Dylan remembered an early – perhaps first – encounter with Chandler, in a room above the Gaslight.

“There’d always be a card game going on. Van Ronk, Stookey, Romney, Hal Waters, Paul Clayton, Luke Faust, Len Chandler and some others would play poker continuously through the night… Chandler told me once, you gotta learn how to bluff, you’ll never make it in this game if you don’t. Sometimes you even have to get caught bluffing. It helps later if you’ve got a winning hand and want some other players to think you might be bluffing.”

Chandler had his own recollection. “When Dylan came to town, he wasn’t writing much. His songs were Woody-esque, songs like, ‘Hey ho Lead Belly, I just want to sing your name,’” a riff on Guthrie’s song in tribute to the unjust trial and execution of Sacco and Vanzetti.

Dylan’s “Song to Woody” was sung to the tune of Guthrie’s “1913 Massacre” and included a phrase from Guthrie’s song, based on a real life tragedy in Calumet, Michigan: Someone maliciously yelled “fire” in a crowded building occupied by striking miners and their families on Christmas Eve. For his sessions at Columbia’s Studio A in November, 1961, Dylan would record “Song To Woody” and another original, “Talkin’ New York,” along with the Van Ronk’s arrangement of “House of the Rising Son,” Eric von Schmitt’s arrangement of “Baby Let Me Follow You Down,” and several more newly-acquired songs, like the spiritual, “Gospel Plow.”

“I hadn’t started writing but know exactly when I did,” said Chandler. “December 15, 1961. I was playing up in Saratoga Springs, New York, and on the front page of the newspapers, The Daily News and The Post there were similar pictures of a terrible school bus accident in Greeley, Colorado. What was so heavy about it, everyone had seen it and the kids messed up on the ground. I wrote about it and played it in my set that night and when I finished, people were just looking at me.”

Leaving the stage, he went to the dressing room, changed into a new shirt, and put his guitar away, “And then the applause started,” he said. “People were pounding on the tables.”

___

Chandler’s song sometimes referred to as “Bus Driver,” about Duane Harms who survived the crash in which the school children died, was never recorded but its melody is known, its existence a talking point in folk circles, ever since Dylan introduced a song he called “Emmett Till” on Cynthia Gooding’s radio show in 1962.

“I stole the melody from Len Chandler. And he’s a funny guy. He’s a folk singer guy. He uses a lot of funny chords you know when he plays and he’s always getting to want me to use some of these chords, you know, trying to teach me new chords all the time…Said don’t those chords sound nice? And I said they sure do, and so I stole it, stole the whole thing.”

The murder of Emmett Till was a catalyzing event in the Civil Rights Movement, entwined with the imminent Southern voter registration drives and the Freedom Rides from the North that would begin in 1961; the bombing of the buses and targeting of civil rights workers would begin soon after. Dylan’s ballad tells the story of the 14-year-old from Chicago who was murdered on summer vacation in Money, Mississippi in 1955. It was a lynching typical of the Jim Crow South, but its aftermath was something else entirely. Till’s mother, Mamie, insisted on an open-casket funeral for all the world to see. Newsprint pictures of a son’s mutilated body and his mother’s grief were purposefully placed across the pages of the national Black newspaper, The Chicago Defender, and Jet, the weekly magazine. As media coverage persisted, the trial proceeded and an all-white jury acquitted Till’s killers. The horror of Till’s murder continued to unfold throughout the ‘50s, including a public confession without legal consequence. The public outcry contributed to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first of several civil rights acts intended to accomplish desegregation and protect the voting rights of African Americans.

“I’d be reading Time Magazine, The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal – we’d sit in bars and I’d be reading the paper and underlining and stuff,” said Chandler.

What Dylan and Chandler shared was an interest in their times, and time spent building the scaffolding for their songs, searching for angles, finding out how to place matters of their times on the page and on the stage.

As with the old time musicians from the early part of the 20th Century they’d heard on Folkways recordings, a song’s sensational details were key – the blood and the hands, the judge and the juries, the scenes where crimes pay or don’t, and the fact life goes on, despite its harms and hard luck endings.

“Both Len and Tom wrote topical songs,” Dylan wrote in Chronicles of Chandler and Tom Paxton, one of the first players in the Village to bolster his set with more original material.“Songs where you’d pick articles out of newspapers, fractured demented stuff—some nun getting married, a high school teacher taking a flying leap off the Brooklyn Bridge, tourists who robbed a gas station, Broadway beauty being beaten and left in the snow, things like that.”

In The Big Money, part of his USA Trilogy, author John Dos Passos marries fiction and non-fiction, headlines, song lyrics, and freely associated inner monologue to depict life in the early part of the 20th Century. Dylan researcher Scott Warmuth has pointed to the ways in which Dylan, through song, painting, film and his memoir has created a similar labyrinth for the century’s second half, conjuring picaresque characters from the Village and its environs, as real life figures, overlapping with embellished characters, found text, images and imaginary and borrowed dialogues.

“The topical headlines that Dylan suggests Chandler was looking at when writing songs are real headlines that Dos Passos incorporated into The Big Money,” notes Warmuth, citing attention grabbers like “some nun getting married,” “Broadway beauty being beaten,” and “tourists who robbed a gas station.”

Warmuth traces further passages in which the Village people and their milieu are described in terms from Mezz Mezzrow’s pulp fiction, Really The Blues. Dylan describes the denizens of the folk scene in the exact language Jack London used in his stories to characterize the temperament of dogs and wolves. Chandler is one of the few figures who managed to escape a canine comparison.

“Besides being a songwriter, he was also a daredevil. One freezing winter’s night I sat behind him on his Vespa motor scooter riding full throttle across the Brooklyn Bridge and my heart just about shot up in my mouth,” wrote Dylan. The story continues, the pair sliding across the bridge in high wind and ice. “I was on edge the whole way, but I could feel like Chandler was in control, his eyes unblinking and centered steadfast. No doubt about it. Heaven was on his side. I’ve only felt like that about a few people.”

“I think Dylan’s new record just came out,” said Chandler. “We took his first record and two guitars on my motor scooter and we went to see Woody Guthrie in the hospital. They didn’t have a record player. And so Woody just put Dylan’s record under his pillow, we took out our guitars and sang Woody songs.”

By 1962, Dylan and Chandler began having their early compositions published in Broadside and Sing Out! the go-to magazines for topical and traditional folk enthusiasts.

“Our neighbors, Rene and Sally, had a Broadside magazine,” said Chandler. They were strumming “Blowin’ In The Wind,” on guitar. “We were on the fire escape on East Broadway smoking a cigarette because my wife didn’t like cigarettes in the house and that was the first time Dylan heard anyone playing one of his songs.”

“A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall” was published a month later in Sing Out!

“When I heard ‘A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall,’ I started playing it and I played it on 12-string in open C-tuning. On a twelve string that’s a lotta Cs, it really sings,” said Chandler.

Poet Allen Ginsberg said he wept when he heard the recording, “…it seemed the torch had been passed to another generation.”

Dylan had gone in further search of how to write what he characterized not as topical nor protest works but rebellion songs, inspired by Tommy Makem and the Clancey Brothers, traditional Irish singers who were also making their way in the Village. Amidst the backdrop of a Cold War and his sense that America was on the verge of a new kind of Civil War, Dylan studied newspaper headlines on microfilm from 1855-1865 at the New York Public Library, “to see what daily life was like.”

—

I think of the time that before us has been

I think of how little each man’s had to spend

I think of how close is my own little end

And I think how my time I’ve been spending *

While at a gig at the Colony Inn in Rhode Island, “Somebody told me Pete Seeger was on the beach and I should go meet him,” said Chandler. “So I’m jogging and I see this big tall figure jogging and it’s Pete and I started telling him about this song I wrote.”

Chandler was struggling to find the right melody to a song about his topic du jour: His wife had been caught in a lobster trap. Seeger told him, “What’s so important about being original? I know thirty different versions to one melody. If you add to a song, it will only extend its great history.”

Chastened by Seeger’s assertion, Chandler was open to learning more about folk tradition. He accepted Seeger’s invitation to the next song conference being organized in Atlanta. Young people were rallying for voting rights and Seeger had commissioned Charles Neblett, Rutha Mae Harris, Bernice Johnson and Cordell Reagon, The Freedom Singers, to raise funds for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to register voters throughout the South. Chandler attended, and found his facility for secular rewrites of spiritual songs on the spot was much a much needed service he could provide to the movement, on marches, at sit-ins, and in jail cells.

“Cordell said, call your wife and tell her you’re not coming home. And I said where am I going? And he said, Arkansas,” said Chandler.

The voting rights campaigns organized by SNCC had continued across the South for a year, from the summer of 1962 and into the summer of 1963, and concentrated in Mississippi in the wake of the June 12 assassination of NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers by the Ku Klux Klan.

One of the song lyrics Chandler rewrote, before he started to write his own melodies became a movement anthem: “Move On Over (Or We’ll Move On Over You)” was sung to the tune of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” its final line trading out “marching on” for “moving on.”

“When I was writing a lot I would aggressively read the papers – highlight – and then go into my quiet place and think about it.” One of the techniques Chandler used was to take a familiar song and hang lyrics on it. “When you really change something, nobody remembers the original melody, if you’ve been skillful,” he said.

There are a few versions of how Dylan got to the voter registration rally event on July 6, 1963 in Greenwood Mississippi. In one, he was invited by the New World Singers – Gil Turner, Happy Traum and Rob Cohen. Or, as actor-singer-activist Theo Bikel tells it, Dylan was writing important songs, songs that could be part of the “arsenal and weaponry” of the movement, but with a caveat: “He doesn’t have first-hand experience or real awareness of what was happening.” Movement workers reasoned he needed to experience the trouble firsthand.

Like Chandler, Bikel had attended Seeger’s song and organizing conferences, had sat in on strategic voter registration sessions, and instructive workshops on being a white ally from the North. Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman at first balked, but Bikel said he would see to it the costs were covered and that he would personally accompany Dylan. He observed the songwriter on the airplane, taking notes “on the backs of envelopes” and performing “Only A Pawn In Their Game” the next day.

A few weeks after Greenwood, a similar cohort of folk performers went to Newport for the annual festival, culminating in what we now know as the archetypal Civil Rights/Folk era moment: Seeger, Peter, Paul and Mary, the Freedom Singers, Dylan and Baez holding hands leading a singalong of “We Shall Overcome” to close out the event. Chandler was not among those assembled in the famous photograph.

“Only through my direct action, after I went to the conference in the South, did I feel like I contributed anything to the movement,” he said. “It wasn’t just because of the marching. It was because I was able to see firsthand all the things that were happening… Lots of people can tell someone to vote but not that many people can perform for 7 8 9, 10, 11, 12,000 people.”

“I would go to the North and work and I’d get enough money together. In other words, I could pay my obligations in New York and we would leave for the South, where you could eat a chicken dinner with three vegetables for a dollar and quarter,” he said.

As the summer ended, Chandler rolled in to DC from Boston to meet the musicians, the movement workers and civil rights leaders gathered at the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Organized by labor organizer A. Phillip Randolph and civil rights activist Bayard Rustin with assistance from Harry Belafonte, a quarter of a million people gathered to insist for equal rights – to work and vote, to live in a country free of racism.

Dylan again performed “Only A Pawn In Their Game” solo and “When The Ship Comes In,” with Baez and Chandler. On guitars and voice, Dylan and Baez accompanied Chandler, who had injured his left hand and needed musical support on his updated lyrics for “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize (Hold On).” A close relative of “Gospel Plow,” with its “hold on” refrain), “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize,” was famously sung by Odetta earlier in the decade and was well on its way to becoming an anthem of the era. The peaceful non-violence masses that Malcolm X had his doubts about singing their way to freedom were doubling down on the fight, their numbers increasing, the messaging growing stronger.

Chandler’s take circled back to the headlines.

Read it in the paper the other day, things are swinging in the USA, keep your eyes on the prize, hold on

“After I did my part, Dylan and I walked away…just walking around, sitting on the edge of one of the monuments, behind the Lincoln memorial, smoking, continuing to talk and then we started hearing Martin doing the “I have a dream” section of his speech, and we said, ‘Hold up hold up, listen to this dude blow, this is wonderful.’ That’s what I remember from the speech, being behind another monument with Dylan and silencing ourselves, and sitting in amazement as we heard that wonderful speech unfold.“

Broad-based coalitions, where race, economic, educational and gender identities intersect have historically been deemed dangerous by the powers that be and the efforts to track the artists, stop their momentum and thwart their influence have been well documented. It happened to Seeger in the McCarthy era, and it would happen again to topical songwriters of the ’60s and beyond.

In 1964, Chandler’s song, “Beans In My Ears,” was recorded by the folk-light group, The Serendipity Singers. It was a hit in some parts of the country, though subsequently pulled from the market when it was discovered there had been a public health emergency created by children actually putting beans in their ears. The Weavers, nevertheless sang it at their farewell concert in 1964, a kind of unofficial end to the folk revival and the beginning of a new epoch for folk rock.

“A lot of people were getting recorded around me and I was the one that was closing the show all the time, and I’m talking about all the time, and I wasn’t getting any nibbles,” said Chandler. He simply wasn’t being courted by record labels like his fellow folkies during the great folk scare of 1958-65.

“I made an appointment to see John Hammond and sang him two songs and he gave me a contract that day. And that was weird: It was good and bad,” said Chandler. “He had no idea what to do with me or around me or anything. He said he welcomed the opportunity to record me as he would have liked to have recorded Lead Belly in his prime.”

Lead Belly, as musically gifted and influential as he was, was not formally trained as a musician. Born on a plantation, Lead Belly served several prison terms between 1915 and 1940, including a stay at Louisiana’s state penitentiary, Angola, before arriving in New York, where he also served a jail term. Chandler was nothing like Lead Belly.

“I got Bruce Langhorne to play guitar with me and Bill Lee to play bass,” said Chandler of his Black accompanists, seasoned session players and veterans of the folk scene, including Dylan’s recordings.

“At Newport that year, I played ‘Shadow Dream Chaser of Rainbows,’” said Chandler. “Somewhere there’s a real stupid review of that night in one of the Newport papers that I wish I still had even though it’s still stupid. It said, ‘Dylan was the showers and Chandler was the rainbow. They were just pissed off because he was playing electric.”

I think of the mazes of folly I’ve run

How randomly chosen how wantonly run

Not for fame nor fortune nor freedom nor fun

Just a shadow dream chaser of rainbows *

At the festival’s “protest song night,” Chandler broke a string and riffed a bit while getting recalibrated. “I said something like, ‘I wish we’d use all the power we have to stop doing the jive things we’re doing in Vietnam and Laos’ and got booed.”

Chandler had shared the stage with Guy Carawan, Bernice Johnson Reagon and Fannie Lou Hamer, the leader of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, whose commitment to voting rights culminated in her speech at the 1964 Democratic convention, protesting Mississippi’s all-white delegation. Her televised appeal and the movement behind her made way for the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Hamer, as it turned out, had sung the way to freedom, turning the spirituals “Go Tell It On The Mountain” and “This Little Light of Mine,” into marching songs.

That year Chandler also wrote an indictment of Governor George Wallace, “Murder on the Road to Alabama,” during the marches from Selma to Montgomery in 1965, following the murder of civil rights worker, Viola Liuzzo.

It you’re fighting for what’s right

if you’re black or if you’re white

you’re a target on the Road to Alabama

The Freedom of Information Act has over the years revealed that countless artists, entertainers, public intellectuals and private citizens were under constant surveillance during and beyond J. Edgar Hoover’s reign of the F.B. I.

“Sonia Sanchez in one of her books was talking about a guy coming to her and saying look, if you lay off this stuff, being an instigator, rabble-rouser, making people less patriotic, your voice will be 100-fold enhanced. If you don’t, you’ll be silenced,” said Chandler. “They really told us, you make a deal. You cut this out and you can have all this.”

He paused to reflect on the memory of Cordell Reagon, the Freedom Singer who’d set him on his own path as a movement singer. “My friend Cordell, they really muscled Cordell big time, to get him to inform or change his road. When I say muscle – harassment, following, steaming open stuff, direct intimidation. I didn’t know it at the time. His wife told me after he died. I think he was killed.”

___

Chandler’s debut album, To Be A Man, was released by Columbia in 1966. With liner notes by Broadside co-founder, Gordon Freisen and song notes by Chandler, the collected originals capture not only a moment when folk–and rock – and the movement –was changing. His songs concerned the philosophy of where it was all going, after the assassinations of JFK and Malcolm X, and before the killings of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Senator Robert Kennedy. Dr. King had admired “Keep on Keeping On,” and even used the phrase in a piece of oratory to address the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. Chandler understood King to have learned the phrase, “keep on keeping on” when one of his secretaries read the lyric in Broadside.

For his second album, The Loving Kind, Hammond brought in producer Elliot Mazer. “It was more of a pop record. What I really would’ve liked to have done was to bring all of my music and tastes, R&B and jazz and classics.” He felt he’d been shoehorned into the pop category, yet again, there was no push from the label.

As the Civil Rights Era was winding down and the Black Power Era winding up, the winds of change sent Chandler in search of something else. He pursued publishing poetry. Black Arts poet David Henderson had introduced Chandler’s work to Langston Hughes and they kept a correspondence until Hughes passed. Having worked on writing songs to accompany a news segment on the Lowndes County Freedom Party, also known as the Black Panthers (the name borrowed for the Black Panther Party founded a year later in Oakland, California), Chandler was hired by Lew Irwin to write topical songs for The Credibility Gap, a new kind of sketch comedy troupe which sent up the social and political worlds. But coincident with the show’s debut on the day of the California primary election in June of 1968, RFK was shot and Chandler was in the position of having to create a musical narrative under tremendous pressure.

His ability to keep spirits moving under fire also served Chandler in his role writing for FTA, a musical-comedy revue that toured military bases in the Pacific Rim at the height of the anti-war movement from 1971-72 with Jane Fonda, Donald Sutherland and a rotating cast that alternately included folk singer Holly Near, comedian Paul Mooney and songwriter Jerry Williams (Swamp Dogg). Chandler can be seen at work throughout the Francine Parker film, FTA. In one powerful sequence, he holds back a line of military police while leading a rousing chorus of his perennial, “Move On Over (Or We’ll Move On Over You).”

We chase after rainbows because we’ve been told

that at each rainbow’s end there’s that great pot of gold

But rainbow gold chasers all forfeit their souls

And the soulless have never cast shadows *

Eventually, Chandler, like Dylan, would make his home out west. He stuck with his craft of songwriting and passed it on to others, becoming a founder and facilitator of the Songwriters Workshop in Hollywood, occasionally grabbing opportunities to write for commercial purpose but usually passing on anything that would mean compromise in order to make big money. Calls would come in for ad jingles, the odd liquor commercial and whatnot, which he’d take as an opportunity to write something satirical, then show up for the presentation to school the mad men in the ad game: “No money down” for diamonds was not a cause he was interested in supporting. In the song game, he’d get calls from the producers seeking hits for their superstar clients: “Whitney Houston…I just couldn’t get it up for that.”

Chandler occasionally performed in the early part of the 21st Century, political fundraisers and benefits for radical left solidarity efforts against perpetual wars and for racial justice. At the time of this interview, he’d sung at a three-day folkathon at UCLA, a reunion of the LA coffeehouse, The Ashgrove, a ’60s and early ’70s hub for acoustic music, progressive politics, way out poetry and folkloric dance, along with the blues, gospel and mountain music legends he had come up with at the folk festivals of yore. Chandler still has much to say about all of it, the then and now of it, as a well-informed, human rights advocate, a self-proclaimed news junkie and daily listener of Amy Goodman’s Democracy Now!

___

In 2008, Chandler, with his wife Olga James (a groundbreaker in her own right as an actor and dancer – she appeared opposite Dorothy Dandridge and Harry Belafonte in the film, Carmen Jones) – worked to elect the young senator from Illinois to the office of President.

“We did phone banking, encouraging people to vote early,” he said. “It makes it less easy to suppress the vote. They had me calling Oregon and Nevada and, after hearing about voting early, we decided to vote early too.”

In 2012, Dylan received the Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest honor awarded to a civilian by President Barack Obama. Through the years, it’s been agreed upon and argued that Dylan moved away from rigorous engagement with issues and topical song after the early ’60s high water years for protest. But it is perhaps more accurate to consider Dylan chose to disassociate from movements and politics, while his songs still brought the news of the isms that plague a troubled America. Paying tribute to common and uncommon people, people like the falsely accused and political prisoners Rubin “Hurricane” Carter and the Black Panthers’ “George Jackson,” Dylan spoke to the people who cared to hear him and hardly turned his back on Black liberation cause. Continuing to dig deep into gospel and blues for inspiration and illumination, Dylan’s 21st Century works Love and Theft, Modern Times and the film, Masked and Anonymous continued to grapple with the complications of Black and white America, then and now.

Chandler has not sought nor received acclaim for his contribution to American democracy, in the fights for equality and racial justice, here and afar. Though he’s occasionally asked to recall the events of the ’60s that shaped him, he declines most opportunities to revisit the Village that made him into a folksinger and then sent him in search of something more. Time still takes time, but change can happen in an instant.

“The people that really will continue to successfully struggle are people who are able to maintain their focus through all the barrage of distractions and keep their eye on the prize,” said Chandler.

Sixty years to the day after he sang at the historic March on Washington, Len Chandler died at home in Los Angeles on August 28, 2023. He was 88 years old.

“Shadow Dream Chaser of Rainbows” by Len Chandler

Filed under: anti-racist, anti-war, Bob Dylan, Civil Rights, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Poetry, Joan Baez, Len Chandler, MLK birthday, MLK Day

Actor, singer and activist Harry Belafonte accepted the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal on Friday night in New York City for outstanding achievement by an African American in 2012. Reprising a powerful speech he delivered at the NAACP Image Awards on February 1 in Los Angeles, he urged Black America, especially its artists, to get involved in the ongoing fight for social and economic justice, particularly in the areas of gun and prison reform, and eradicating poverty.

Actor, singer and activist Harry Belafonte accepted the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal on Friday night in New York City for outstanding achievement by an African American in 2012. Reprising a powerful speech he delivered at the NAACP Image Awards on February 1 in Los Angeles, he urged Black America, especially its artists, to get involved in the ongoing fight for social and economic justice, particularly in the areas of gun and prison reform, and eradicating poverty. America has there be such a harvest of truly gifted and powerfully celebrated artists. Yet, our nation hungers for their radical song. In the field of sports, our presence dominates. In the landscape of corporate power we have more of a presence of captains and leaders of industry than we have ever known. Yet, we suffer still from abject poverty and moral malnutrition.”

America has there be such a harvest of truly gifted and powerfully celebrated artists. Yet, our nation hungers for their radical song. In the field of sports, our presence dominates. In the landscape of corporate power we have more of a presence of captains and leaders of industry than we have ever known. Yet, we suffer still from abject poverty and moral malnutrition.”

Lead Belly was born around this day of January in 1888 or nine. This is a portion of his story, adapted from my Crawdaddy! column, The Origin of Song.

Lead Belly was born around this day of January in 1888 or nine. This is a portion of his story, adapted from my Crawdaddy! column, The Origin of Song.