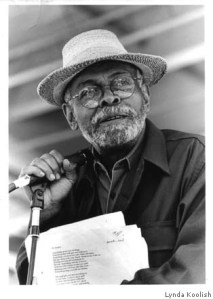

Jazz musician Les McCann died of pneumonia in Los Angeles on December 29, 2023 at age 88. As a leader and sideman, he recorded countless albums and made major contributions to the soul-jazz music of the ’60s and ’70s. His piano work has also been sampled frequently in the modern hip hop era. McCann has been most often remembered and celebrated for his performance of the Eugene McDaniels song, “Compared To What.” Performed live with Eddie Harris at the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1969 and released on their album, Swiss Movement, McCann on vocals and piano gave the song a certain punch and swagger. This is an edited transcript of my talk with McCann, about the origin of the song – widely considered to be the greatest protest song of the Vietnam era – and his thoughts on life in 2016, from his then 80-year-old vantage point. May he rest in peace – with condolences to his surviving loved ones and friends.

“When I began my career in LA we had immediate attention. And whenever you have attention, you have other people coming around, trying to get your attention. I was performing with my trio at LA City College and Eugene McDaniels came by one night. I didn’t know who he was, but he liked what were doing and started hanging out. I thought he was the greatest male voice I’d ever heard. I invited him to join my group.

We started working together, and the money wasn’t good, but it was the beginning of us being professionals. He was different from all of us. He could speak English. A lot of people who didn’t like him, didn’t like him because of that. He was a very bright man, very clever. He knew what he was doing and he went after it. I believe he was the son of a pastor.

We were kinda like friends, he’d sit in, but we also hung out. We had a vocal group, a choir, and we’d get together and sing, 12 people, but all were potentially looking for their own career. When he came to us, and said, “I got a record deal, they gave me a lot of money,” we were happy for him, but not only did he stop singing the music we loved for him to do, he started doing all these other things. When they offered him the big money, some people thought he was being a traitor to jazz. But we were all just trying to make it. I was his reminder, the one who told him, don’t forget where you came from, don’t forget why you’re here.

He didn’t know he was a songwriter, but he’d ask me what I thought: Everything he showed me was unbelievable. I didn’t know he loved Bob Dylan. When I first heard “Compared To What,” it was just a set of words, there was no music. It had the words “God dammit” in it, and it was one of the reasons stations wouldn’t play it. No one had ever done that before. They were his words and I was speaking them: This was Gene son of a preacher, questioning whether he should speak his truth, which involved speaking words a preacher’s son shouldn’t say. It also involved a man speaking perfect English and being Black.

I could do what I wanted on my record label and so I recorded the song. But it was nothing like it was six years later when we did it on Swiss Movement. All that happened right there. We were just doing what we thought was great. It took me six years, but the way everyone now hears it happened in a moment, instantly onstage.

_____

“We think we’re unique, that nobody knows what we go through, but it’s not about the singing it’s about being a human, living in this world. These are lessons on learning how to love, trying to find our place and be who we are…You need to deal with the fear and the bullshit. We’re taught to be afraid of everything. Don’t do this or that: It’s said on purpose, part of the curriculum of this earthly school. Everyone has a blueprint, everyone sets out to do their thing. It’s all here, for us to learn. I’ve never stopped learning.

Earth ain’t meant to be heaven. We’re all angels having an earthly experience. Everything you can think of happens right here on this earth. If it wasn’t for sex and money and fighting, there would be no problems. It’s all how you look at things. We all have intuition.The real truth is in the quiet of who you are. I walk hand in hand with who I really am.

I remember my other lifetimes. I don’t want to do the same things over and over. It might take many times but the choice is whether we decide to live in love or in the things we fear.

Every time you do an interview, ask yourself the questions you want the answers to, ask everything you want to know of yourself: You’ll hear things you never heard before. You already know all this. It’s not anything you haven’t heard before.

Fear or love.

You have go through it and deal with it.

It’s how get to where we want to be by the time we die.

Did we really answer the call?

Did you live the life you wanted to live?”

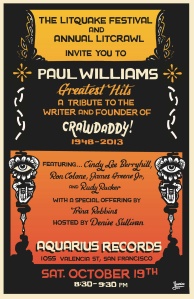

c. 2016, Denise Sullivan

Filed under: anti-racist, anti-war, Arts and Culture, Jazz, Obituary, Origin of Song, Soul, Compared to What, Eddie Harris, Eugene McDaniels, Les McCann, life lessons

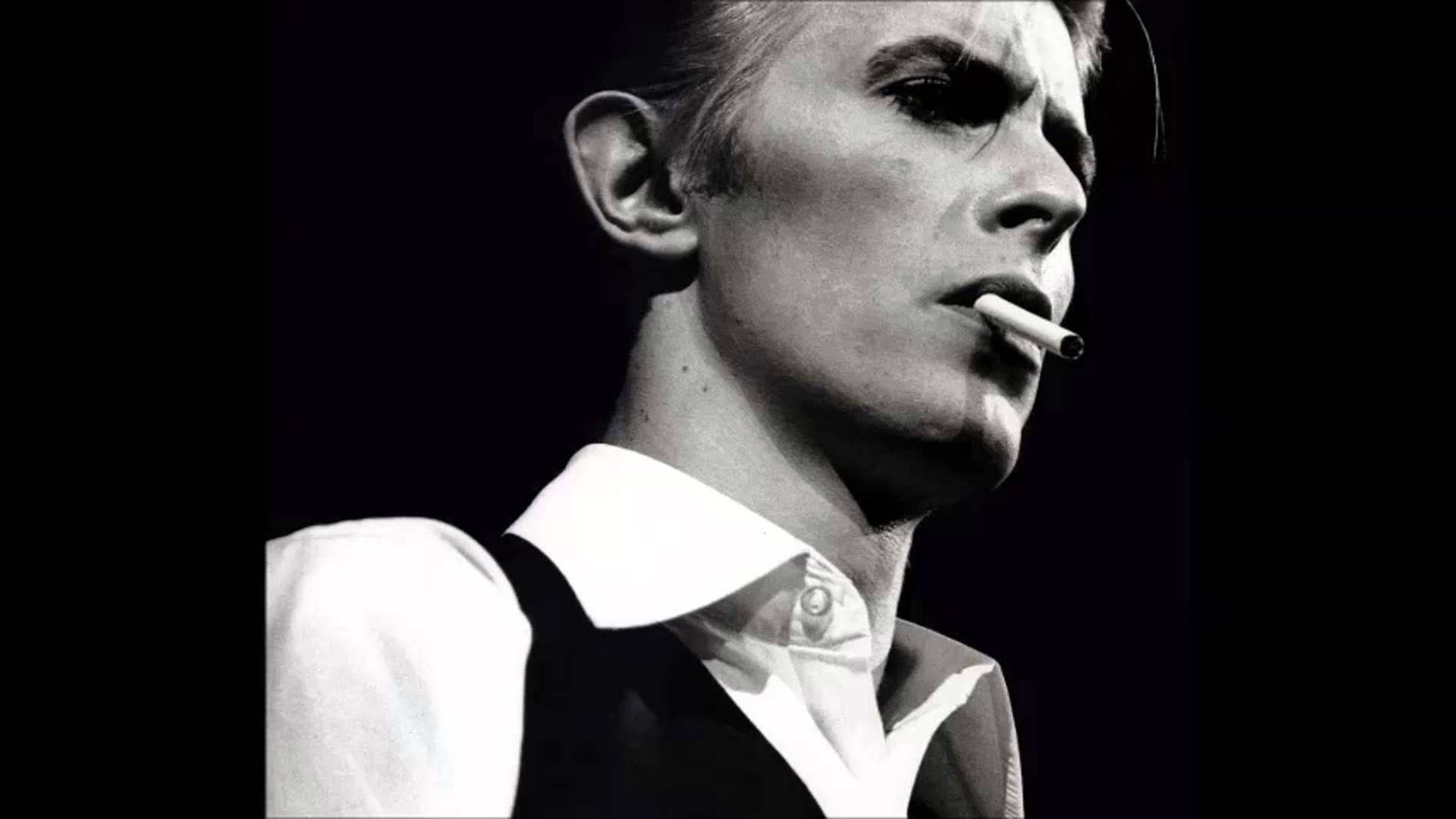

It’s been a day of mourning throughout the rock’n’roll nation: David Bowie, 69, died last night. The worldwide outpouring of grief transcended racial, gender and sexual orientation, economic, and national boundaries, just as the Brixton-born artist’s music did. The last thing any of us need are more words or further analysis of an already well-documented life and depth of the art: Bowie’s creative expression of rebellion will ring in the hearts of anyone with their mind set on freedom for generations to come. And now here goes anyway…

It’s been a day of mourning throughout the rock’n’roll nation: David Bowie, 69, died last night. The worldwide outpouring of grief transcended racial, gender and sexual orientation, economic, and national boundaries, just as the Brixton-born artist’s music did. The last thing any of us need are more words or further analysis of an already well-documented life and depth of the art: Bowie’s creative expression of rebellion will ring in the hearts of anyone with their mind set on freedom for generations to come. And now here goes anyway…