This piece originally ran as an Origin of Song column in Crawdaddy! in the Spring of 2010. It’s time to play it again, man.

This piece originally ran as an Origin of Song column in Crawdaddy! in the Spring of 2010. It’s time to play it again, man.

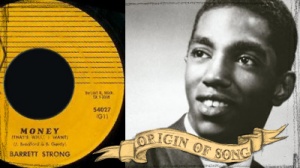

These unprecedented times of bail-outs and world economic crisis have me thinking a lot on money: Who’s got it, who doesn’t, how they got it, and how I can get my hands on some of it. Money. That’s what I want. Which is how I’ve come to consider the case of Barrett Strong.

Born February 5, 1941 in Hard Times, Mississippi, you know him as the songwriting partner of Norman Whitfield and all those right-on Motown hits: “War” (“Good God! What is it good for? Absolutely nothing”); “Smiling Faces Sometimes” (“They don’t tell the truth”); “Psychedelic Shack” (“That’s where it’s at”), “Cloud Nine,” (“I’m doing fine”); “Ball of Confusion (That’s What the World Is Today)” and “Heard it Through the Grapevine.” The guys were geniuses, Songwriting Hall of Famers and all that, but, before the string of hits, he was strong out the gate: The Beatles knew him as the guy who sang “Money (That’s What I Want).” He was the one who came up with the riff and scored the first hit record for a then-brand new little label called Tamla, and chances are you’ve heard the rest. If not, check this:

Tired of earning pennies on the dollar for writing songs for Detroit’s R&B pride, Jackie Wilson, songwriter Berry Gordy switched over to music’s business side. In competition with his sister Anna and the record label that was her namesake, he formed his own label, Tamla, his roster consisting almost entirely of kids from around the way, with a few notes from his own songbook. Distributed by Anna, by June of 1960, “Money (That’s What I Want”—written by Strong, with credit taken by Gordy and Janie Bradford and performed by Barrett Strong—was the company’s first national hit, reaching number two on the R&B charts and crossing over to the Top 40. It turned out to be as prophetic as it was strong: “Well now give me money (that’s what I want)… I wanna be free.” Not long after that, Gordy’s friend and label VP, Smokey Robinson, sold a million copies of “Shop Around” with his group the Miracles. The self-contained, family-like, black-owned business from the Motor City delivered “The Sound of Young America” to the world with its especially designed blend of pop and R&B, intended to steer the singers away from the sounds of the stratified R&B chart ghetto and into the spotlight, where American Dreams were made. Sadly, many of Motown’s own were shorted on their share of their contributions—and those details are being worked out and worked over to this very day.

Back then, people used to love the idea of made-in-America music and all that American dream stuff, especially in England, which is how the Beatles fit in: The song first showed up in their sets during their stay in Hamburg, Germany as a crash-bang encore. In the Beatles Anthology, George recalls first hearing Strong’s single in Brian Epstein’s record shop; Ringo notes they all had the same records anyway, and “Money” was likely one of them. Included on their famously rejected demo for Decca Records, it was eventually released and closed their second album, With the Beatles, alongside two more Motown songs: “Please Mr. Postman”, originally cut by the Marvellettes, and Smokey Robinson’s “You Really Got A Hold On Me” (adding up to a bonus for Mr. Gordy). Listen and you’ll hear Ringo playing just a bit heavier as the band emphasizes the riffing—which is how it got to be known as one of the original hard rock songs. Perhaps it sounds quaint these days, but just listen to how they rock it, especially in the final choruses: In comparison to their songs at the time, “Money” was nuts—and people like nuts—and it was even a bump up the nut scale from “Twist and Shout.”

More on “Money” and how it came to define the Beat sound of the early ‘60s can be discovered at this quick one stop source for Beatle stuff. Additionally, the in-your-face essence of “Money (That’s What I Want)” suited John’s image as the impatient, angry, and snotty head Beatle, and earned him a rep as the group’s rocker; it was a fact that got up “the cute one” Paul’s nose since he too was capable of ripping it up, Little Richard style, as in his performance of “Long Tall Sally.”

Meanwhile, back in Dee-troit, as he famously called it in one of his songs, John Lee Hooker came out with “I Need Some Money”, the very same Barrett Strong song, releasing it the same month that Tamla was having a national hit with it, and delivering it in John Lee mostly one-chord boogie-style.

As time went on, they were doing the “Money” dance in London (the Who and Led Zeppelin), up in Washington state (Pearl Jam and the Sonics), and don’t forget the motor city—where there was dancing in the streets to versions by Strong’s Motown labelmates the Supremes and Junior Walker and the All Stars.

In the ‘70s, it became cool to bad-rap greenbacks—something to do with the cynicism of the decade’s great recession, which was—as surely you remember or perhaps as you’ve heard—the worst since the Great Depression (ha!). In 1973, Pink Floyd went Biblical with it: (“Money is the root of all evil”) in their “Money”, with its cash register ka-ching sound effects. And oh, the sarcasm: “New car, caviar, four-star daydream, think I’ll buy me a football team.” So, too, to the Bible did go, the O’Jays (“I know that money is the root of all evil”) when they Gamble and Huff-ed their way through “For the Love of Money,” an anti-song to the “lean, mean green,” also from 1973. A couple of years later, still suffering from the post-recession-boho-blues, Patti Smith wrote about dreaming of winning lotteries and robbing banks in “Free Money.” Even Abba took the rich man to task in “Money, Money, Money.”

But by 1979, memory of the oil crisis and resulting ecological awareness that marked the ‘70s was starting to fade and money madness was coming back in style. The spirit of Gordy and Strong’s song came back in an ultra-cynical form as performed by the Flying Lizards, with a version that bridged the gap between punk rock desperation and the go-go ‘80s. Of all the renditions, it seems to be the one that enjoys the most spins today, turning up in movies and on television. The usages, as they say in the business, all generate a lot of green for Gordy. From then until now, there were plenty of money-positive songs going around, songs about material girls in the material world, and tough guys getting paid in full, making bank. I personally liked “Gimme Some Money,” Spinal Tap’s send-up of “Money (That’s What I Want).”

Sometimes I regret not boarding the gravy train, but most days I’m happy to feel like Paul McCartney did (‘til he became rich) when he supposedly wrote “Can’t Buy Me Love”, to counter the cash-grabby “Money (That’s What I Want).” But when times are hard, who doesn’t like to dream about free money? So try saying it out loud with me: “Money (That’s What I Want).” It worked for Berry Gordy and Barrett Strong, the Flying Lizards and the Beatles. Say it again: “Money (That’s What I Want).” I like to tell myself, like Swamp Dogg says, “I’m not selling out, I’m buying in.” So say it, one more time y’all: “Money (That’s What I Want).” I think I like the sound of that tune.

Filed under: Rhythm & Blues, Roots of Rock'n'Soul, Swamp Dogg, "I Need Some Money", "Money (That's What I Want), Barrett Strong, hard times, John Lee Hooker, money making mantra, Plastic Ono Band "Money", songs about money, Whitfield and Strong, world wide economic crisis