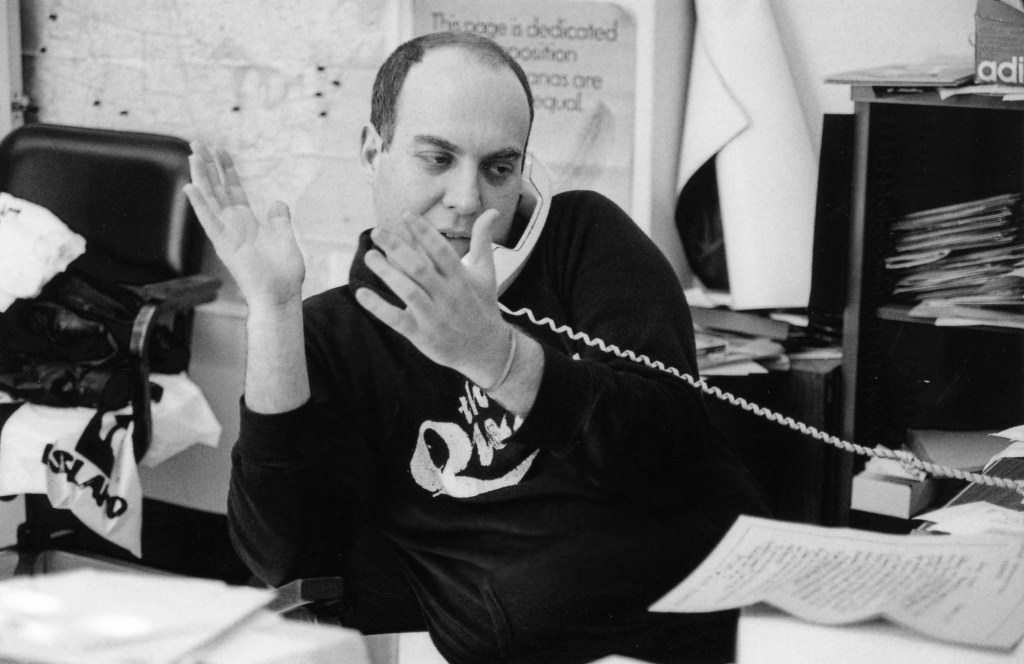

Writer, political activist, broadcaster, and record man Howie Klein’s life was large, unique and apparently complete as it came to a close on December 24. The work, his work–what some might call magic–was largely invisible, so much of it occurring out of the public eye, yet he leaves an indelible imprint on politics and culture, both on the underground and in the mainstream, as well on the individual lives he touched. Boiling down his life and legacy to a few paragraphs or simple words isn’t possible, especially today, Christmas, one day after he left our present reality for parts unknown. It’s particularly poignant that he should exit at this time of year when I think he secretly loved the holiday (his longtime annual Christmas shift as Howie Klaus on KUSF-FM was the giveaway).

Following an outstanding career in the record business in which he became known as an artist and First Amendment advocate, he spent the past 20 years fighting fascism as a commentator and as an ally for politically progressive candidates, while tending to several bouts of long term illness.

I met Howie about 45 years ago, when I was still a teenager, though before that, I heard his voice on the radio, broadcasting on KSAN-FM from the Sex Pistols final concert at Winterland. Lucky for us, he’s left behind a catalog of his life and times on the hippie trail, at Harvey Milk’s camera store, at Neil Young’s Broken Arrow Ranch and on the White House dancefloor, in writing and images, all to be compiled for publication as a memoir (more news on that in the new year). For now, I send love and condolences to all who knew and cared for him and leave you with his own words, on what it means to write and remember.

HOWIE KLEIN: So, as you probably know, I’m trying to write this memoir… but I don’t have the greatest memory in the world. Neither do most of my friends. Neither do most people in general it turns out. I explained how this has been impacting my work when I wrote about DEVO and Dolly Parton last month. How did “Mr B’s Ballroom” get written? My recollection was that I brought DEVO there and they wrote the song. My friend Michael Snyder, who I brought there, said DEVO wasn’t with us and that we told DEVO about the place and Mark Mothersbaugh wrote the song afterwards. I called Mark and he confirmed Michael’s version. I had such vivid “memories” of DEVO aghast at “Mr. B’s!”

I don’t remember exactly when I read Anne Rice’s Interview With A Vampire but I remember where I read it— San Francisco… and I remember discussing it with Harvey Milk, who was assassinated in 1978, so it was probably that year or the year before. No one had to tell me that the vampire myth was a metaphor for homosexuality long before Anne Rice came along and I was explaining that to Harvey while I was reading the book, which isn’t nearly as queer as the new TV series running on AMC now.

In that series (the 3rd episode), Daniel Molloy is interviewing Louis de Pointe du Lac in his Dubai penthouse and Louis seems to say that Lestat was the actual creator of “Wolverine Blues,” the jazz classic by Jelly Roll Morton, recorded in 1923. Daniel gets pissed off and accuses Louis of being an unreliable witness. As a defense, Louis explains the theory of the “odyssey of recollection” by reading from Daniel’s own memoir: “I am in my Buick, staring in the rearview mirror at my daughter in the car seat, an hour after I gave Derek, a guy I don’t know, the last 30 bucks I had. My editor reminds me, it’s seven years before car seats are mandatory. My ex-wife reminds me, I never owned a Buick. This is the odyssey of recollection.”

Sometimes there’s irrefutable— more or less— evidence, proof. That Iceland story I wrote was based on a daily diary I kept of our visit to the island early in 1969. When I asked Martha, now an internationally renowned neuroscientist, then my girl friend and traveling companion, what she thought of the page I posted about the trip, she had no recollection of Mario and Frances, the two American professors we met on the plane who asked us to chip in with them for a car and explore the country. We were with them for over a week, had plenty of adventures and dramas. Martha couldn’t even recall their existence.

I also sent [a] photo of Martha and Autumn Haze at our off-campus house in Rocky Point on Long Island (probably 1967 or ’68). Martha and Autumn didn’t like each other at all; they kind of tolerated each other. So this was a sweet and rare photo I found of them. I asked Martha what she recalls about the photo. She immediately remembered her blouse, she told me. She said she doesn’t recall I had a dog.

Memory does not work like a recording device. Elizabeth Loftus is a psychologist and memory expert, specializing in studying false memories. She explains her work in this TED Talk in Scotland, which has been viewed by over 5.8 million people on the Ted Talk site and another 2 million on YouTube. “Our memories,” she said, “are constructive. They’re reconstructive. Memory works a little bit more like a Wikipedia page: You can go in there and change it, but so can other people.” She discusses misinformation in this talk three years before Trump slithered into the White House.

She concluded her talk with the kind of statement that must be the bane of every memoir writer: “Most people cherish their memories, know that they represent their identity, who they are, where they came from. And I appreciate that. I feel that way too. But I know from my work how much fiction is already in there. If I’ve learned anything from these decades of working on these problems, it’s this: just because somebody tells you something and they say it with confidence, just because they say it with lots of detail, just because they express emotion when they say it, it doesn’t mean that it really happened. We can’t reliably distinguish true memories from false memories. We need independent corroboration.”

In 1802 William Wordsworth wrote “The Rainbow” (also known as ‘My Heart Leaps Up’) which was published in 1807. In high school we were asked to memorize the last three lines, which are also featured in the even more famous “Ode: Imitations of Immortality,” which Wordsworth started the day after he wrote “The Rainbow.”

My heart leaps up when I behold

A rainbow in the sky:

So was it when my life began;

So is it now I am a man;

So be it when I shall grow old,

Or let me die!

The Child is father of the Man;

I could wish my days to be

Bound each to each by natural piety.

©Howie Klein

Filed under: Obituary, Punk, rock 'n' roll, books, Howie Klein, life, memoir, memory, music business, political activist, writing