Back in the Paleolithic era, I worked as front desk receptionist for concert promoter Bill Graham and had several encounters with members of the Grateful Dead family. Not that I knew who they were at the time: it was a big part of my identity as a modern music lover to not know, though I’ve come around to their sound and specifically to Jerry Garcia.

For the sake of a prequel and partial sequel to the business at hand, I accidentally experienced the Dead at a Day on the Green concert in 1976 when they co-headlined with The Who. At the time I didn’t know or care that the big events staged at Oakland’s stadium would became a kind of testing ground for the full scale festival tours we know today. It didn’t help I didn’t know “Scarlett Begonias” from “China Cat Sunflower” or to that to my unformed mind, experiencing the Dead was just a three hour endurance test before the Who hit the stage. I was not transformed, my consciousness was not altered by their music, as some members of the band and the people who love them claim, though today, I quite like most all of Garcia’s and lyricist Robert Hunter’s material. I like to think I have grown into it.

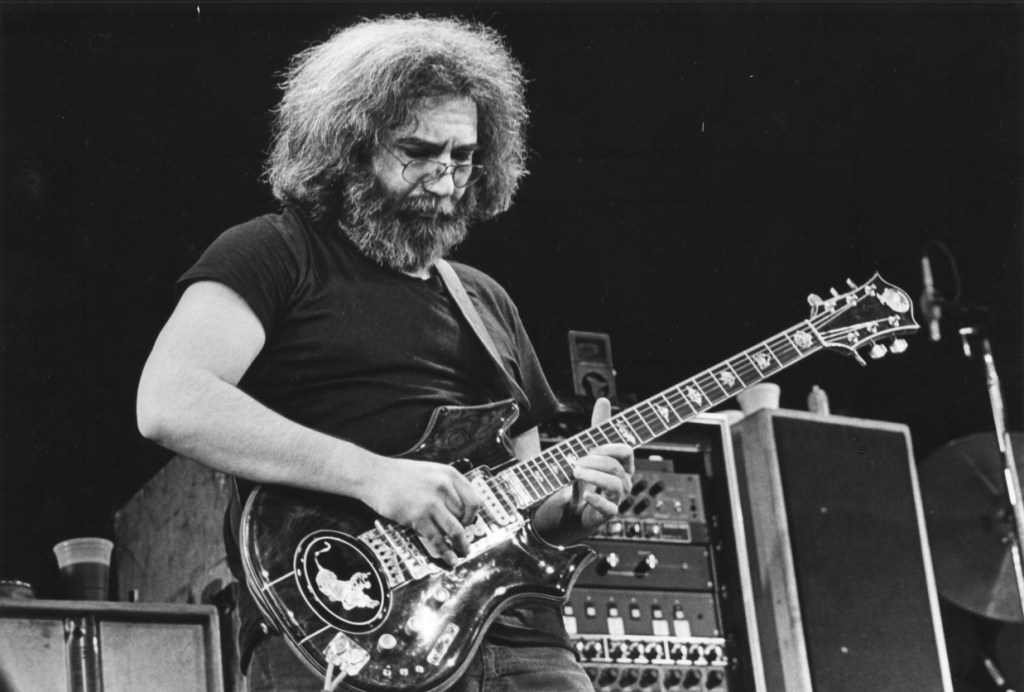

But even back when, I knew Jerry was Jerry, and later in my role as receptionist, I certainly knew enough about receiving office visitors that I was not to waylay people of his renown at the entrance with formalities like announcing their arrival. In the flash it took me to recognize a musician, he could walk past me, nod, and in Jerry’s case, with his cherubic smile, head bowed and hands jammed in his pockets, proceed without pause, into the open main office, then in the direction of Bill’s corner sanctum. Same went for Carlos. Santana. He and Jerry were of course legends by then, their reputations enshrined thanks to their inimitable, celestial guitar styles. I was less generous about their music then, but showed respect anyway: These were people born in the same decade as my parents. Then again, I can’t claim to have displayed anything resembling even courtesy the day an even older man dressed in a fur loin cloth and carrying a walking stick announced his arrival.

“Bear for Bill.”

“Excuse me?”

I couldn’t hide my contempt, buzzing over the line to Bill’s assistant.

“Someone named Bear is here for Bill?”

“Send him in.”

The shock registered on my face compelled a co-worker witnessing the scene to whisper my way.

“Bear is Owsley.”

“And?”

“He invented acid.”

I get it now.

On another day, Mountain Girl announced herself. My lack of exposure to hippie culture was pitiable and the name drew a complete blank. I said something like, “Say what now?” I feel sorry for being just one more person to judge Carolyn Garcia based on her chosen name and hope she can forgive me. Perhaps we might even agree that Jerry would be “rolling in his grave” in connection with some of events of the last few weeks celebrating the 60th anniversary of the formation of the Grateful Dead.

Thirty years ago, on August 9, 1995, Jerry Garcia died. His diabetes raged, his heart gave out and his body failed him while detoxing from a lifetime of drug dependence. A few days later, his life was celebrated with a public memorial concert in Golden Gate Park. By that time, the Dead had been doing big business for some time, thanks to constant touring and their first top 40 hit, “A Touch of Gray.” Never mind then that Garcia’s health was down and his addictions were up: The show must go on as the Dead’s touring, merch and ticket sales were doing the kind of big boring business the music industry represents today.

The bands formed in Jerry’s wake include The Other Ones, The Dead, Further, Ratdog, Phil Lesh & Friends and the Rhythm Devils (there are more). But the extreme monetization of all things rock ’n’ roll, psychedelic and Dead had been well under way for several decades. The Grateful Dead as corporation was just another aspect of its long strangely quirky and contradictory trip.

Beginning in 2015, Dead members Bob Weir and Mickey Hart began billing themselves Dead & Company; by 2023, they played to bid goodbye to touring with their Fare Thee Well shows. Those dates, according to published accounts in music industry trade magazines and other media outlets, grossed $114.7 million over 28 shows, though they were hardly the end. In 2024, Weir, Hart and an amalgamation of musicians played a 30 show stand at the Sphere in Las Vegas and earned $130 million that year as Dead & Company. This year’s Dead & Company returned from the dead, again, for 18 shows at the Sphere and three in Golden Gate Park to mark the 60th anniversary of the formation of the Grateful Dead and 30 years since Jerry’s passing. The tour receipts for this year have not yet been published, though some fiscal facts are known.

Tickets for the Golden Gate Park weekend ranged from $600 for three days and went up to $7k for the VIP Package. The concerts brought $150 million to the city’s economy, $7 million into the Parks and Recreation Dept. according to local media, and some untold sum for promoter, Another Planet Entertainment, not to mention the band, its agents, managers and other profiteers. I don’t know much about the Grateful Dead but I’ve read the books and can tell you that profit was not a big motivator when the band was founded. Money and possessions were seemingly of little interest to Garcia.

To say it another way, Dead & Company do not embody the spirit of the Dead and its commitment to alternatives to commercialism and mainstream culture. That is if there is such a thing as a spirit of a band: In the Dead’s case, that bird has definitely flown. I can say more, much more, but won’t now except: In 1996 I spent six weeks on the road with the Further festival. It was unpleasant to say the least and I survived it by immersing myself in nightly sets by Los Lobos, a band I am certain has a spirit because I can feel it.

And yet, there are still some traces of Jerry’s spirit around if you are looking for it in the city that raised him. Whether its the makeshift shrines in the Haight, stenciled Jerry bears on sidewalks around town, or the annual Jerry Day free concert at McLaren Park, I could swear some days, especially in August which marks his birth and death, he hovers.

Jerry Day was established in 2003 to celebrate the Excelsior District’s most famous son; this year a street there was named for him. But the future of Jerry Day is imperiled due to “lack of funding” and city support. How could this be in a city of 80 billionaires? How could this be in a city whose mayor is worth millions made from the profits of Levi Strauss, the jeans favored by hippies and punks and everyone else, you may ask and I will answer: We are a city that creates and then commodifies everything: From rock ’n’ roll, psychedelics, and cannabis, to the Grateful Dead, to mention but a fraction of what comes from Northern California. We even have a Counterculture Museum to keep the idea of an underground in place.

No, I don’t blame the latest generation who want to partake in their own rituals or a virtual tribal love rock musical: It’s the cost to play the game I can’t relate to. There’s also the carbon in/carbon out trucking and busing of staging and sound equipment on public park grounds, our much-needed oasis in a largely concrete residential neighborhood that’s hard to get your head around.

Jerry loved Golden Gate Park. It’s east to west world map of flora and fauna literally inspired his guitar playing. But following the three dates of Dead & Company there, the three-day Outside Lands festival and last week’s straight vanilla “alt-country” event, the concerts have trampled the landscape and turned the largely working class, Democratic voting blocks of the outer Richmond and outer Sunset neighborhoods into a parking lot. And we did nothing to prevent it. Oh sure, we voted to make the Great Highway a park, but we got very little in return for that either.

The highway, its nearby grid of avenues, and the park itself, were built on sand dunes. They were not designed with an in and out flow of 60,000 non-residents a day in mind. These neighborhoods of families, people with disabilities, seniors and people of all ages who speak more languages than in any other area of the city are boxed in. Many of us are in the work force and use the roads to travel to and from our jobs. There are hospitals and other services that bookend the park and people need access. And then there is the wildlife that has been displaced for a month by top volumes, distracting spotlights, and cyclone fencing not to mention the human footprints marring their paths home.

Jerry used the park himself to find peace and quiet: That’s where he was found one morning in his car in 1985 with a shit ton of drugs on him and in him (in 2025, concert goers in the park enjoy the brain freezing drug of nitrous oxide). Communing with nature takes many forms but the combination of numbing out in these times seems less like a tribute and more like a cop-out.

Granted, my distress is not about the disruption outside my window but is intertwined with the upheavals worldwide. If you’re reading this, you wake up screaming in some form or another, whether about detainment, displacement, about the genocides, dictatorships, rolled back rights and the current incompetence at most levels of leadership [release the files]. And yet these cries are signs of our human connection, our consciousness, the kind once encouraged by the Dead or psychedelics or a combination of the two.

Even though now it seems like no one is listening, those of us who are awake and alive are the miracles we are seeking. The shakedown, whether in the park, at the Dead & Company HQ or on the national stage is just another version of life in all its stages: good, bad, ugly and beautiful. So I keep doing what I do. Live my life accordingly. Sometimes I ask myself, what would Jerry do? And while I choose not to check out, I can’t deny we’re living in a blast furnace. Yet I see no choice but to play it through, and just keep truckin’ on.

Filed under: anti-capitalist, anti-racist, anti-war, Arts and Culture, California, rock 'n' roll, Rock Birthdays, San Francisco News, Billionaires, Golden Gate Park, Grateful Dead, Jerry Garcia, music, robert-hunter