I have an image of him in the late ’50s: Still underage, he sneaks through the curtains at the front door of the hungry i, the Keystone Korner or the Purple Onion, slinks into one of the seats in back, and gets lost in music.

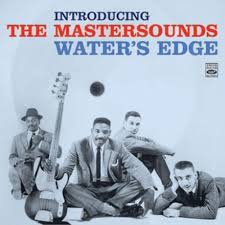

He must’ve told me of the nights he went to hear Dave Brubeck, Gil Evans, Gerry Mulligan, and The Mastersounds, with Wes Montgomery. But it wasn’t until he died that I understood what it meant to be there at that time: North Beach, San Francisco, probably 1958 or ’59. The Beats had arrived by then–outlaw heroes like Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg passed through as did my dad, the cleanest cut kid in the joint. Lenny Bruce would’ve called him “Jim,” the comedian’s nickname for a straight, but my dad was no square: I like to think of the original hipsters welcoming him in, an innocent among them for the night.

He must’ve told me of the nights he went to hear Dave Brubeck, Gil Evans, Gerry Mulligan, and The Mastersounds, with Wes Montgomery. But it wasn’t until he died that I understood what it meant to be there at that time: North Beach, San Francisco, probably 1958 or ’59. The Beats had arrived by then–outlaw heroes like Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg passed through as did my dad, the cleanest cut kid in the joint. Lenny Bruce would’ve called him “Jim,” the comedian’s nickname for a straight, but my dad was no square: I like to think of the original hipsters welcoming him in, an innocent among them for the night.

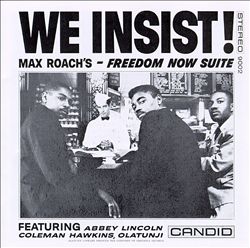

As a child, I didn’t grasp that my dad was a jazz fan, though his stack of interesting looking records were his only possessions I ever admired. I realize now that his was a modest-sized collection, though it was very tidy, very specific and literally very, very cool. It was Cool Jazz, also known as West Coast, that my dad favored. He had every recording by the Modern Jazz Quartet featuring Milt Jackson. I guess he liked Jackson’s vibraphone because Cal Tjader’s records were also well represented, as were MJQ sound-a-likes the Mastersounds with Buddy Montgomery on vibes, and his brother Monk on bass, and sometimes Wes on guitar. Piano jazz also rated on his scale–Brubeck was a hero, as was iconoclast Ahmad Jamal. And there were even stranger sounding names to this kid–Joao Gilberto, Antonio Carlos Jobim and Laurindo Almeida–with their pronunciations that confounded me, and their breezy bossa nova guitars that captured the scene at Ipanema Beach. And then there were the Stans: Getz and Kenton, alongside tenor sax man, Rahsaan Roland Kirk (who was still just Roland back then). Flipping through the stacks, I felt like I knew these jazzmen, in a way other kids might’ve known Frank Sinatra or Bob Dylan; they were a part of the family.

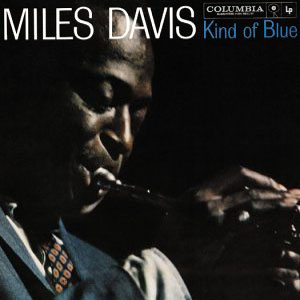

It was the colorful, modern art-inspired album covers on the Verve, Prestige, Argo, and Fantasy labels that first drew me in, long before I knew anything about musical shapes, colors or subtleties, and all the shades they could throw. I think of putting one of those records on the turntable now, pouring over the liner notes and getting lost myself, while holding an actual Blue Note or Impulse! sleeve, instead of a reissued imitation. And yes, I could pick up a copy of one or two at a vintage vinyl store but it’s my dad’s records I want, with his energy, the stories of their purchase, and a recounting of the historic gigs where the songs came alive for him. I also want his enthusiasm for my taste for the avant-garde and for my similarly small, tidy and very cool stack of Alice Coltrane, Ornette Coleman and Sun Ra. But even if he were here to sit with me, I don’t know that he’d be all that interested in talking jazz because somewhere along the way he left behind his passion for it.

By the mid ‘60s, more and more fans of Cool Jazz had turned to hard bop and rock’n’roll. Times had changed, The City, as it’s known, had been psychedelicized. My dad was now living as a young suburban family man. A periodic drinker who put down the bottle long enough to regain his vision from time to time, he became a health food nut, a jogger and a tennis bum, long before all three things helped define the laidback ‘70s. “Over-committed,” is how he referred to the house, the yard, the two kids and three cars— his life, between jobs, outside San Francisco. Naturally there was no nightlife to pursue, no trips to town to hear music; most of the old clubs had gone dark by then anyway. And so he spent a fair share of time at home, sleeping in the hammock, sitting at the kitchen table, pouring coffee, typing mysterious reports and letters on the old Royal, watering the lawn, but never touching the stack of vinyl or the phonograph, even though it was positioned to be within easy reach of the California-style kitchen-family room-patio. It was as if the simple act of putting a needle to a record was too much trouble.

Occasionally, he’d ignite the old jazz flame: He once took me to see Cal Tjader locally, though teenage me couldn’t understand why a so-called legend should be playing in the St. Francis High School gym. My brother has a similar story: Was it Milt Jackson at the Grand Opening of the Mayfield Mall? I don’t know, I have to ask him. And if dad ever dug the music in the air, he’d partake of that strange jazzer’s custom, the finger click (shoulders hunched). Sometimes while driving, he’d find the jazz spot on the radio and start bopping, gesturing with an occasional air-cymbal crash. For me, these small acts were simultaneously embarrassing and ethereal: Jazz made life bearable for a moment as we floated, refreshed, for a couple of beats or bars.

When my dad moved out of the house at the end of the ‘70s my mom gave his records to a young jazz enthusiast, a boy she thought would appreciate them; our jazz days were over and so was our family. And yet the LPs—their covers, their vibraphone, horn and piano sounds, and their longwinded notes on the people who played them—occupy a significant space in my heart and light my way in the darkness. Sometimes I wonder had he lived, if my dad would’ve rediscovered his passion for jazz. And if only it had occurred to me when he died in the ‘80s to have played a little Louis Armstrong at his funeral. If he was with us today, would he have succumbed to the Quiet Storm? Or would he hold strong and enjoy classic Mingus and Monk with me? For sure we would agree that Duke is the king, and we certainly would’ve gone to see Ahmad Jamal when he rolled through town last week. But would he still put on that ridiculous posture as he be-bopped down the hall, and would I reflexively roll my eyes like I did as a teenager when he paused by my bedroom door, approving of the horn charts of Blood, Sweat and Tears and Chicago? Hard to say. I’ll never know. Though whatever the mood, and whether we agreed or not, it would all be ok by me—if only he was here right now. Because what I really need to ask him, what I really want to know, is if he can remember the moment he stopped listening.

When my dad moved out of the house at the end of the ‘70s my mom gave his records to a young jazz enthusiast, a boy she thought would appreciate them; our jazz days were over and so was our family. And yet the LPs—their covers, their vibraphone, horn and piano sounds, and their longwinded notes on the people who played them—occupy a significant space in my heart and light my way in the darkness. Sometimes I wonder had he lived, if my dad would’ve rediscovered his passion for jazz. And if only it had occurred to me when he died in the ‘80s to have played a little Louis Armstrong at his funeral. If he was with us today, would he have succumbed to the Quiet Storm? Or would he hold strong and enjoy classic Mingus and Monk with me? For sure we would agree that Duke is the king, and we certainly would’ve gone to see Ahmad Jamal when he rolled through town last week. But would he still put on that ridiculous posture as he be-bopped down the hall, and would I reflexively roll my eyes like I did as a teenager when he paused by my bedroom door, approving of the horn charts of Blood, Sweat and Tears and Chicago? Hard to say. I’ll never know. Though whatever the mood, and whether we agreed or not, it would all be ok by me—if only he was here right now. Because what I really need to ask him, what I really want to know, is if he can remember the moment he stopped listening.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Qc3VaXtW5M

Filed under: Jazz, Dads who like jazz, different kind of post, Father's Day, Personal Essay Collection Sunny Side Up